My wife and I rarely have disagreements.

One of the thorniest issues in our entire 17 years of marriage has been protein.

Yes. Protein. As in collections of amino acids that are part of our diet. As in something that is needed (in at least some amount) for the growth and repair of body tissues.

At times, protein has been a loaded word in our relationship. Dangerous enough to shut down an entire conversation and cause one of us sleep on the couch. And prevalent enough that we often joke about the Taco Bell protein commercial, which may be the best commercial ever recorded.

And while protein seems like a nutritional issue, there are so many personal finance aspects to it as well. Protein costs money. And as I’ll discuss soon, not eating enough protein can cost you a ton of money (and your life).

Table of Contents

- How protein came to affect my marriage

- Why you should care about protein

- My protein scare

- What is a “high protein food”

- Are high protein foods expensive?

- Summary- Eating for health and wealth without breaking the bank

Please do not confuse my personal blog for financial advice, tax advice or an official position of the U.S. Government. This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase after clicking on a link, I get a small percentage of the sale at no additional cost to you.

Special disclaimer: I am not a doctor or a nutritionist and this is certainly not medical or diet advice. I’ve tried to link to original scientific literature wherever possible.

How protein came to affect my marriage

My wife is amazing. She is constantly thinking about our family’s diet and whether or not we are eating a nutritious and healthy meal plan.

When I was diagnosed with celiac disease 15 years ago (long before the “gluten free fad”) she read a billion cookbooks and completely revamped our meal plans.

She is also a big fan of Michael Pollan books and food documentaries. For many years, you could say our diet was encapsulated by Michael’s suggestion of “Eat food, mostly plants, not too much”. Eventually, we switched “mostly plants” to “nearly all plants” when we became vegetarians (close to vegan) in the late 2010’s. From May to November my wife improvises amazing meals out of what we get from gardens and the boxes of vegetables from the community-supported-agriculture farm we support.

If you want to see examples of our diet, you can see lots of pictures in our post about our grocery budget or pictures of our grocery shopping trips.)

While I’m pretty sure that our all-from-scratch-plant-based diet is probably healthier than 95% of Americans, the non-vegetarian friends and relatives in our life seem very concerned about how much protein we are eating.

If you read a lot of the vegan literature (which seemed good when I read it the first time but now seems like propaganda to me in hindsight) you’d come across statements like, “nearly all Americans eat too much protein” and “spinach is a high protein food”. Both of which are half-truths that I’ll address later in the post.

In America today, it seems like the only nutritional information you can find comes with a worldview (paleo/vegan/intermittent fasting/etc). All of these different dietary tribes seem to focus on telling you why the other nutrition strategies suck rather than pointing out that 90% of the nutritional advice is the same between the diets.

It’s no wonder that it’s impossible to find an answer to a simple question like “am I getting enough protein” without getting completely disorientated. Likewise, questioning something like protein puts people on the defensive because nutrition is now linked with our identity.

Why you should care about protein

I know lifting weights is a contentious topic in personal finance. Who can forget Mr. Money Mustache’s salads and barbells tweet? (While this Tweet was controversial when it came out at the start of Covid, it seems to have aged well).

Don’t worry, I’m not going to go all “burpees and pushups cure depression” or some other insane personal finance bro cliché. But I do want to talk about the importance of strength.

How strong you are and your VO2max are two of the best predictors of all-cause mortality. This paper by Mandsager blows my mind (see figure 2). While smoking or diabetes raise your risk of dying by ~40%, having a low VO2max increases your risk by 390% compared to someone with a high VO2max.

And while if you’re a healthy adult it’s hard to imagine, 7 people per hour die from falling in the United States. Whether you are 3 or 30, falling down usually results in nothing more than some bruises and a bruised ego. However, once you are old enough to start collecting Medicare, falls become a serious injury and cause of mortality.

Why muscle mass in your 40s is so important

Hopefully I’ve convinced you that having enough muscle tissue is a pretty large component of both your lifespan AND your healthspan (how long you are able to live a relatively normal life). If you look at those grip-strength studies, nearly all 30 year olds have enough strength to put them in the lowest mortality category. So what’s the big deal??

According to this excellent review by Keller and Engelhardt, adults lose between 1-5% of their muscle mass per year after age 50. (That’s a big range, but many of the papers show around a 2% decrease per year)

In finance we’re always talking about the magic of compounding. This is the magic of compounding in reverse.

If we take the most common strength loss of 2% per year, you can expect to lose about 50% of your strength between ages 50 and 85.

In other words, if you want to have the mobility and strength of an average 50 year old when you’re in your 80’s, you need to be completely ripped in your 40s before you start losing muscle mass.

I still don’t get what this has to do with protein

So I’ve spent most of this article talking about muscle mass and why you need to care about building strength as part of your midlife crisis. But what does this have to do with protein?

For a long time, I thought that as long as I got the recommended daily allowance (RDA) set by USDA, I was getting enough protein.

The protein RDA for someone of my age and gender is 56 g.

However, I recently became aware that the International Society of Sports Nutrition recommends that people who exercise should eat 1.4-2.0 grams of protein per kilograms of body mass to maintain muscle breakdown after exercise and maximize muscle protein synthesis. For someone of my size (75 kg) that’s 150 g of protein per day… nearly 3 times the RDA.

My protein scare

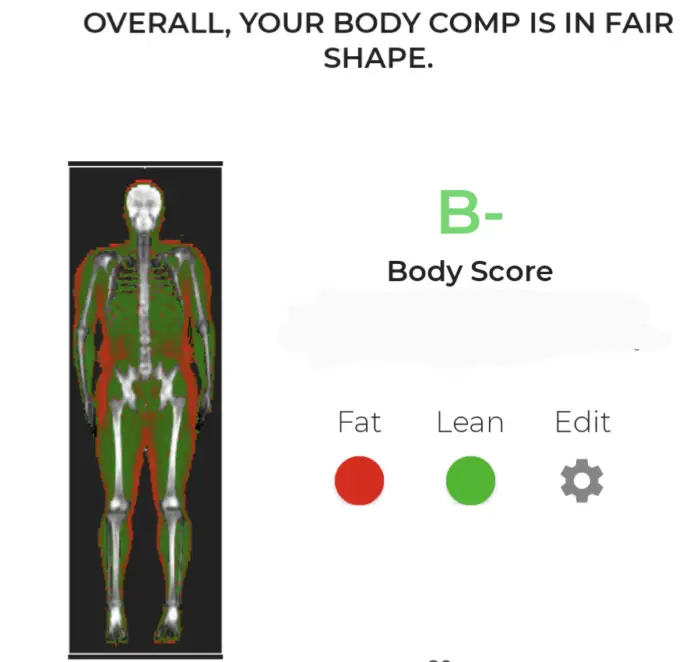

This all became a lot less academic for me earlier this year. I decided to get a DEXA scan to get a baseline of my body composition and see if there was anything I should work on as I age.

I had assumed I was in great shape for someone who is almost 40. I frequently place in the top 3 runners in my age group in local trail races and I try to lift weights a couple times a week on the days I’m not running. I knew that I put on a few extra pounds during Covid but I wasn’t too worried about it because I assumed at least some of it was muscle.

Unfortunately, the DEXA scan told me otherwise. Not only did I have more body fat than I thought (26%) but I also had a below average amount of lean mass for someone in my “peer group”. (To be fair, I have no idea what my “peer group” is.) While I had thought I was moving through the world as a fit person, the reality was that my body composition was not great. In fact, the DEXA scan gave me a health score of B- because of my below average muscle mass, above average amount of body fat, and high amount of visceral fat.

I realized that if this is what my body looks like under the hood at 40, I’m guessing I’m not going to be the 80 year old I want to be…

As a result, I started trying to track what I ate and focus on doing whatever I can to increase my lean body mass before I turn 50 and start my exponential muscle decay.

What I learned about my diet

Within the first hour of tracking my food, I realized how hard it was going to be for me to get the 150 grams of protein per day that the ISSN recommends someone my size get. (I couldn’t imagine being a 220 pound athlete trying to eat 2 grams of protein per kilo of body mass.) If I had to guess, I think I was probably eating 60-80 g of protein per day over the past few years, but not much more.

Working to double my protein intake recently has caused me to learn a lot about the compositions of foods we take for granted every day.

What is a “high protein food”

If you walk down the aisle at the grocery store, nearly every food will have a claim that it is a “high protein food”. Or it will put the protein content on the front of the box and proudly proclaim that it contains 6 grams of protein. And everyone knows you should have peanut butter for a snack because it’s high in protein.

On the other extreme, vegans will tell you that spinach and spirulina (an algae that tastes like barf) are the highest protein foods on the planet.

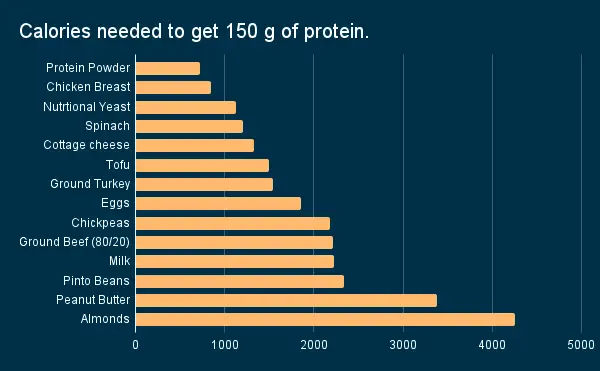

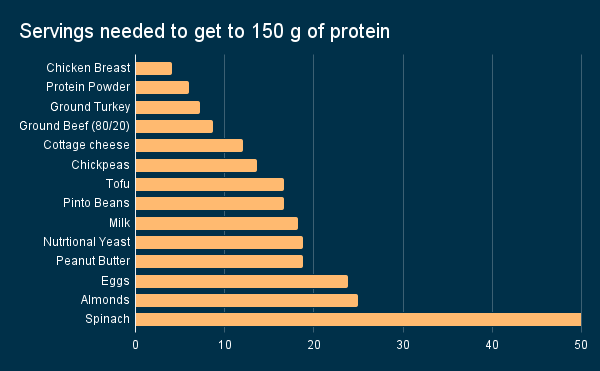

With all of these crazy claims, it’s hard to tell what is a good source of protein. So I did what I always do when I try to understand something. I made a spreadsheet.

Protein optimization from a finance nerd

So let’s start by looking at a “high protein food” by the different ways you could define it.

Yes. Spinach is an incredibly high protein food on a calorie per gram of protein basis. In fact 55% of the calories in spinach come from protein. However, to get 150 grams of protein from eating spinach, I would need to eat 52 servings of spinach a day (my stomach is already revolting).

On the other hand, peanut butter, everyone’s favorite protein snack, has a decent 8 g per serving of peanut butter. But I’d need to eat over 3,300 calories of just peanut butter to get my 150 grams per day.

So while both peanut butter and spinach are “high protein” in their own way, we need a better definition of a high protein food.

I define a high protein food as a food as doing well in both of these two metrics:

- ratio protein to total calories (higher as better)

- grams of protein per serving (higher is better)

Obviously, spinach does great on the first metric but not the second metric, and peanut butter is okay on the second metric but horrible on the first metric.

I made some graphs to compare different foods with these metrics.

As someone that is trying to eat around 3,000 calories (± 20%) per day, you can see that these high protein foods need to make up most of my diet for me to get 150 grams of protein per day per day. (Eat a single bowl of cereal and you can fuggedaboutit).

I also find the vegan literature about beans and spinach being high protein foods kind of laughable when examined through this lens. Sure, you could in theory get your protein requirement by eating 10 cups of beans a day. I eat more beans than anyone else I know and even I can’t eat more than 2-3 cups per day without being completely full.

Are high protein foods expensive?

As someone that care about both health AND finance, the cost of my dietary choices are important to me. We’re a family that eats a gluten free diet for $1.50 per person per meal. Is my new high protein diet going to break the bank?

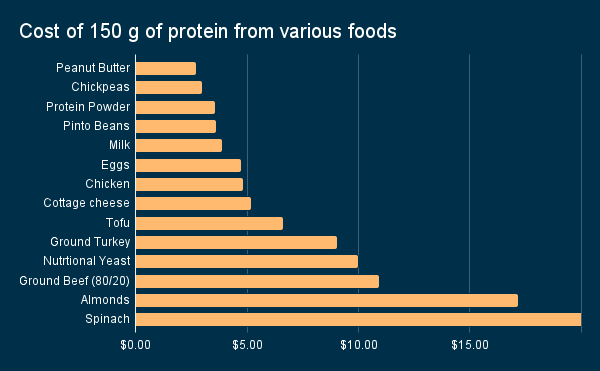

This was probably the most interesting part of my analysis. One of the worst protein sources (peanut butter) in terms of grams of protein per calorie are actually the cheapest.

You could get 150 grams of protein (and a whopping 3300 calories) for less than $3.00.

And while I grumble every time I shell out money for unflavored pea protein powder (the cheapest source I could find), it is actually quite an economical protein source at $3.56 per 150 grams of protein.

Finally- you would need to eat a whopping $81 worth of spinach, the vegan’s favorite “high protein food”, each day to get 150 grams of protein.

Summary- Eating for health and wealth without breaking the bank

I don’t feel that my 2021 diet was unhealthy. But after my DEXA scan and thinking about how I want to age, I felt that I should target eating 2 g per kg of body mass per day of protein.

Over the past few months I have shifted my diet to reach those goals. I’m still a lacto-ovo vegetarian along with the rest of my family. However, I have started hitting the milk and cottage cheese pretty heavy and added 1-2 pea protein shakes per day to my diet.

These foods hit my sweet spot of being protein dense and cost effective.

Even with all of those changes, it’s still pretty damn hard to hit 150 g of protein per day. And this added protein is still costing our family more money, even though we’ve focused on eating only the most economical protein sources.

It’s clear that there are several foods that will allow you to reach a protein consumption of 150 g per day for less than $5. However, that’s only taking care of one of your macro nutrients.

In reality, if you want to get 150 g of protein in a day, you’d be hard pressed to stick to our family’s frugal budget. However, a high protein diet does not necessarily mean an expensive diet.

And finally, if you have no idea how much protein you get in a day, you might want to try to track your macros and see where you come out. (Please do not do this if you have ever had an eating disorder). I was shocked to find out how little protein I consumed in an average day.